Profiting from Corp Governance "Dark Arts": Part 2

Case Study: J. Crew, TPG co-CEO Jim Coulter, and TPG's Infamous Takeout

Welcome to the Nongaap Newsletter! I’m Mike, an ex-activist investor, who writes about tech, corporate governance, the power & friction of incentives, strategy, board dynamics, and the occasional activist fight.

If you’re reading this but haven’t subscribed, I hope you consider joining me on this journey.

Welcome to Part 2 of the ongoing Corporate Governance “Dark Arts” series.

Hopefully you had a chance to read Part 1 which provides the basics and high-level concepts of the “Dark Arts”. If not, I provide a summary below but still encourage you to read Part 1 for more thorough explanations.

For Part 2, I’ll be focusing on a case study that features TPG, their co-CEO Jim Coulter, and their infamous acquisition of J. Crew (announced 2010). Yes, the acquisition occurred 10 years ago, but it’s a phenomenal situation to study. Many of the lessons and tactics that occurred here are still relevant today.

I’m going to walk you through the “how” and “why” of certain “dark” actions at J. Crew and discuss/speculate the consequences/results of those actions.

Disclaimer: This case study is for educational and entertainment purposes only. Contrary to a running joke on Twitter, I don’t actually hate TPG. Although to be fair, I do kind of call them Voldemort/Darth Vader in this post but it’s a joke (really).

TLDR Summary of Part 1 (Feel Free to Skip if Read Part 1)

Part 1 of Corporate Governance “Dark Arts” series focuses on the basics and high-level concepts of “dark” governance actions on the Board (especially actions tied to compensation).

The primary goal of this series is to expose you to “good” corporate governance by showing you how people use the “Dark Arts”.

I define the “Dark Arts” as actions that distort Management-Board-Shareholder alignment to primarily benefit insiders (who engage in the “dark” action) and to gain disproportionate control and/or influence over the governance process.

This does not necessarily mean the “Dark Arts” are illegal.

Compensation is the most important area to understand when examining corporate governance “Dark Arts”.

Compensation best practices noticeably die first when exposed to “dark” actions. That’s your signal to examine the situation closer.

The compensation committee chair is arguably the most powerful “independent” position on the Board, and can singlehandedly distort the power dynamics of the entire Board.

Of all the “dark” actions, monitoring equity grants is the most important. In particular, pay extra attention to “spring loading” and “bullet dodging” behavior.

Manipulating the timing of equity grants relative to material news releases is an easy way for insiders to capture value in excess of “target value”. If you can recognize the signs of this practice, you can profitably participate alongside. No, the SEC does not appear interested in cracking down on this behavior.

Why Case Studies?

There’s a terrific article/book excerpt (2011) I recommend titled: “The Mystery of Expertise”. It highlights how achieving expertise in certain topics/areas requires developing implicit skills that are difficult to explicitly explain.

For instance, the Japanese invented a method of sexing chicks known as vent sexing that quickly determines the sex of one-day-old hatchlings. The challenge of the method was that none of the experts could clearly explain it through explicit instruction. The solution was to train students through a trial-and-error master/apprentice model:

The master would stand over the apprentice and watch. The student would pick up a chick, examine its rear, and toss it into one bin or the other. The master would give feedback: yes or no. After weeks of this activity, the student's brain was trained to a masterful — albeit unconscious — level.

A similar apprentice/master training process was applied by the British during WWII to spot friendly vs. enemy bombers:

With a little ingenuity, the British finally figured out how to successfully train new spotters: by trial-and-error feedback. A novice would hazard a guess and an expert would say yes or no. Eventually the novices became, like their mentors, vessels of the mysterious, ineffable expertise.

One of the main takeaways of “The Mystery of Expertise” is that the apprentice/master trial-and-error model can be a good way of narrowing the gap between knowledge and awareness of certain subjects that rely on implicit skills to master.

I’m not saying I’m a “master” at recognizing the “Dark Arts”, but there is definitely an element of “I know it when I see it”.

Case studies are a good way of blending the explicit lessons from Part 1 with the implicit skills needed to pick up on the materiality of “dark” governance actions.

As I mentioned in Part 1, the most important explicit lesson to remember is pay attention to are changes in compensation:

Changes in compensation and grant timing are “tells” (to borrow a poker term) so it’s important to understand the “why” behind those changes. Usually the changes means nothing, but occasionally it hints to something very material.

The “why” is everything but it’s the hardest (for me) to explicitly teach/explain. I could highlight greed as a major factor to “why”, but it doesn’t fully capture the interplay of social contracts and self-interest between Board members that lead to “dark” actions occurring.

Hopefully this case study give you a better understanding of the “why” and helps you in your own journey to implicitly understand the “Dark Arts”.

Why TPG?

Simply put, TPG is really good at governance “Dark Arts”.

They know how to push the governance envelope to drive their agenda, and are one of the best at playing the game of corporate governance.

I find studying TPG cases useful because:

Personal Familiarity - Studying TPG is how I picked up the subtleties of the “Dark Arts” so it’s easy for me to get up-to-speed on new TPG governance situations.

Robust History - TPG considers themselves “the largest governance laboratory in the world”. Consequently, there are a lot of companies to study. The J. Crew case I highlight is a decade old, but what occurred here (i.e. tactics, modus operandi, etc.) echoes at other TPG governance situations I have come across.

Diversity of Cases - All the TPG governance cases I’m aware of have recurring themes and tactics, but each situation produces unique takeaways to learn from which makes them perfect to feature in this series.

Again, this does not mean their conduct is illegal, and there are certainly more egregious and/or explicitly bad governance actions done by others.

What makes TPG unique is their ability to implement subtle governance actions that most stakeholders don’t realize “slow boils the [governance] frog” to TPG’s benefit. At least with the more egregious individuals/firms, you know you’re voluntarily stepping into a governance mess from day-one and have your guard up accordingly.

TPG’s ability to get away with “dark” actions while still credibly presenting themselves as one of the “good” governance guys is remarkable. It’s the ultimate “Dark Art” when you think about it. Virtue signaling “good” while quietly pushing (often cutthroat) self-interested agendas using “dark” actions takes a lot of cleverness and skill.

Former TPG executive Bill McGlashan was (in my opinion) the poster child of blending “light” (good) with “dark” before getting caught up in the FBI college bribery scandal. Although this case focuses on co-CEO Jim Coulter, I’ll definitely be writing about Bill McGlashan sometime in the future.

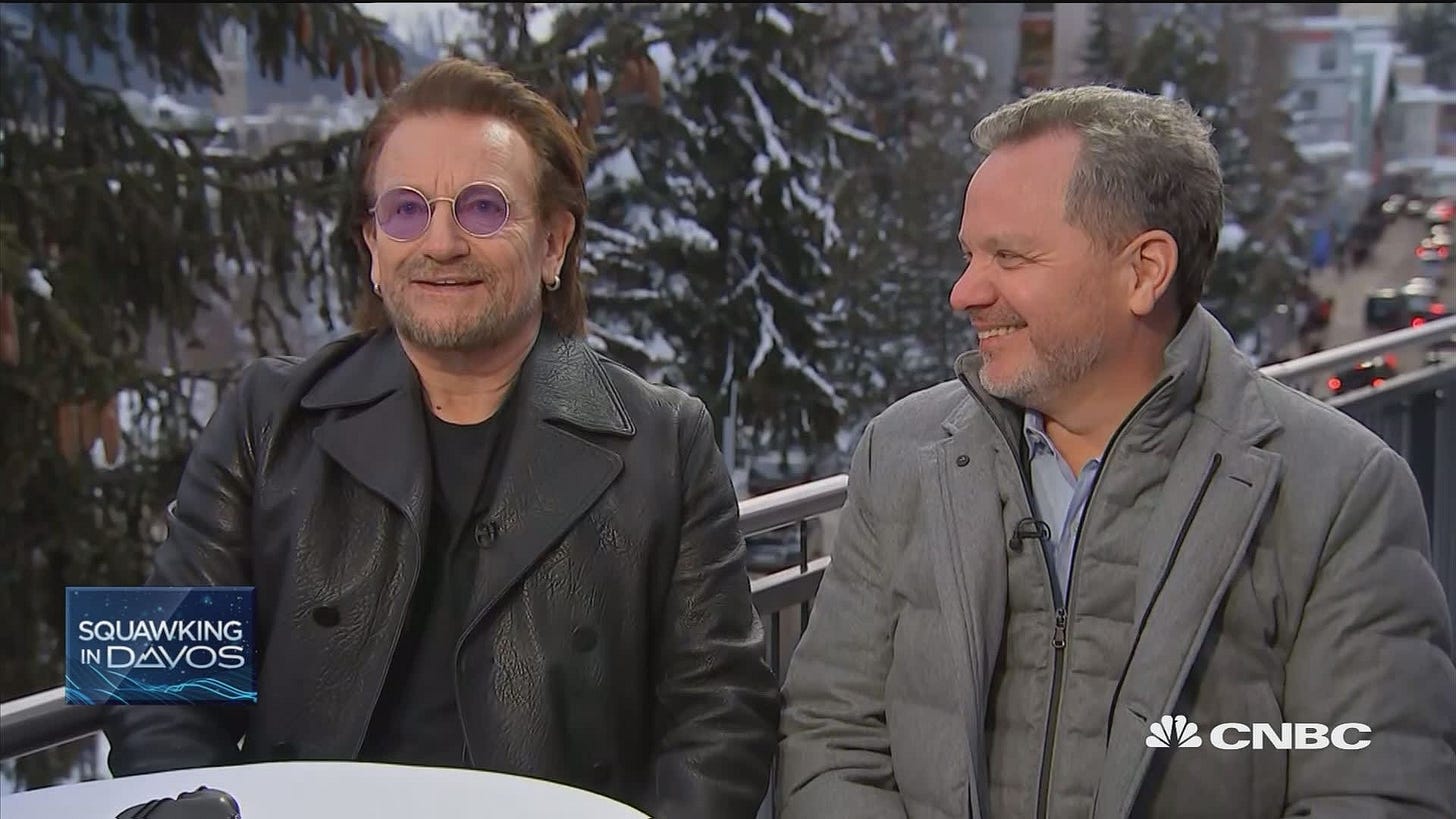

Pictured: Bono with former TPG executive Bill McGlashan discussing the need to fight poverty at Davos( January 2019).

On a side note, given their world class skills in the “Dark Arts”, I find it humorous TPG recently announced their intention to raise a public equity fund that focuses on improving public company governance practices:

“Private equity giant TPG is raising a fund to invest in public companies and will offer its experience to aid better decision making.”

“The fund will seek board seats and provide advice on addressing a range of corporate governance and environmental issues.”

“While that may sound like an activist play, TPG’s new fund won’t write attack letters, launch proxy fights or agitate for management changes.”

For the Harry Potter fans out there, this is kind of like Voldemort and the Death Eaters being put in charge of Defense Against the Dark Arts. Or for the Star Wars fans, Darth Vader teaching new Jedi the Light Side of the Force.

TPG co-CEO Jim Coulter at Bloomberg’s The Year Ahead Summit

Tongue-in-cheek jokes aside, I do recommend you listen to TPG co-CEO Jim Coulter’s talk on corporate governance (and other topics) at Bloomberg’s The Year Ahead Summit. It provides an interesting glimpse into his thinking on corporate governance.

Here’s a snippet of Jim Coulter’s views:

“My entire career has been about governance in the world of [considering shareholders] ‘and’ [stakeholders].”

One thing that really isn’t understood about private equity is that it’s essentially a governance system at its core.

For 25 years, Jim Coulter has been co-running the “largest governance laboratory in the world”. Hundreds of companies, hundreds of board seats, through the most difficult times, CEO changes, IPOs, transactions, etc.

“We’ve got [governance] right, we’ve got it wrong, but we learned a ton.”

“We have never been asked to speak at [governance] conferences.”

Need to fix: 1) shareholder engagement, 2) board dynamics, 3) measurement, and 4) attitude.

TPG searched Linkedin to find as many “governance leaders” and found out none of them have been on Boards. World of governance doesn’t have “practitioners” involved.

“Put investors on Boards.”

Measure not by what we say but by our action.

My main takeaway from Jim Coulter’s talk:

I agree with a lot of Jim Coulter’s points, especially when he says measure by action and not words.

TPG is an extremely sophisticated governance operation built on decades of experience. Every governance action they take should be viewed with that sophistication and experience in mind. They are opinionated in their approach and do things with a specific intent in mind.

If a governance change (even the most subtle change) occurs at a Board with TPG executives involved, pay attention. They’re telling you something is likely going on and you need to understand the “why” behind the change.

Understanding TPG’s “Why” and “How”

Before we jump into the J. Crew case study, let’s quickly discuss the “why” and “how” of TPG’s “dark” actions. This is my speculation based on studying various TPG governance situations.

“Why” would TPG engage in the “Dark Arts” of corporate governance?

In my opinion, their actions tend to be broadly driven by:

Management Flow: Keeping management (especially the ones that have already made TPG a lot of money) happy is a major driver. They prioritize being “management friendly” and go out of their way to compensate management teams very well (egregious amounts at times in my opinion). This creates long-term franchise value for TPG as they strive to have “top of mind” awareness for top tier operators evaluating future opportunities.

Deal Flow: Keeping management happy also feeds into better deal flow. Operators want to work with TPG given how they prioritize management, and often times those management teams will give TPG first look and/or preferential access to their own deals. Having access to top tier operators also gives them more confidence to pursue and/or bid on prospective deals.

Profit: Superior management flow and deal flow should (in theory) drive long-term outsized profits. TPG will also do what is necessary at the Board level to optimize valuation as they exit a position.

Problems and misalignment tend to arise when TPG places their priorities ahead of the long-term interests of the (public) Company.

“How” does TPG engage in the “Dark Arts” of corporate governance?

Remember how I previously said Compensation Committee Chair is the most powerful “independent” seat on the Board?

It is not a coincidence TPG tries to effectively control the compensation committee and have a TPG executive serve as chair of the committee. This is by design and based on experience that comes from being on hundreds of Boards.

By having a TPG executive serve as compensation committee chair, they control the Company’s compensation agenda. And by controlling the Company’s compensation agenda, they have disproportionate influence on decision-making and can distort the power dynamics of the Board.

Specifically, as Compensation Chair TPG can control equity grant size, type, timing, and vesting which gives them a strong one-to-one relationship with the CEO and creates a power dynamic that allows them to separately engage with the CEO without other Directors knowing the full extent of why certain actions or changes took place.

Look at enough TPG cases and you’ll start smelling variations of quid pro quo.

Keep the “how” and “whys” in mind as we go through the J. Crew case study.

J. Crew and the Infamous Takeout by TPG

TPG’s J. Crew acquisition occurred nearly 10 years ago, but anyone serious about understanding the “Dark Arts” must study what happened here. TPG co-CEO Jim Coulter is a “Dark Arts” governance genius in the way he used his position on the Board to quietly architect an acquisition of the Company.

If you’re unfamiliar with the infamous circumstances surrounding TPG’s re-acquisition of J. Crew, I highly recommend you read the Proxy’s Background of the Merger.

I say “re-acquisition” because TPG previously acquired J. Crew in 1997 and took the Company public in 2006. Although TPG exited a couple years after J. Crew went public, co-CEO Jim Coulter remained on the Board and served as Compensation Committee Chair.

Much of the controversy of the deal (rightfully) focuses on what happened between August 2010 through October 2010, and the 7 weeks it took CEO Mickey Drexler to inform the Board he (and the management team) was discussing a buyout with TPG and Leonard Green.

As noted by the WSJ:

Mickey Drexler and representatives of PE firm Leonard Green met in late August 2010 – with TPG acting as a middleman - where they “discussed, on a highly preliminary basis, a potential leveraged buyout of the Company”.

Drexler and TPG co-founder Jim Coulter (who sits on J. Crew’s Board) had dinner on Sept. 1 following a J. Crew Board meeting where the topic of TPG's interest in a J. Crew takeover was also raised.

Drexler and J. Crew CFO James Scully met or talked on the phone several times throughout September 2010 with TPG officials, including TPG’s Coulter. At one meeting, “representatives of TPG were provided certain non-public information about the Company,” including expectations for earnings for the rest of the year.

Only between Oct. 7-11 -- about seven weeks from Drexler’s first meeting with Leonard Green -– did Drexler then contact other Board members to discuss potential takeover interest in J. Crew, and Drexler’s possible involvement in a deal.

In late October 2010, Drexler told a committee of J. Crew directors overseeing a possible sale of the company that he “had significant reservations about the prospect of working for a new boss” if J. Crew were sold. Drexler said, however, that “he had a high comfort level with TPG and had a positive experience with them during the period in which TPG owned the Company.”

Drexler’s statement appears to give TPG and Leonard Green an edge over any other possible bidders, since having Drexler (considered a superstar executive) involved was likely an important factor for other acquirers.

Needless to say, there were lawsuits involved following the announcement of the deal over the flawed M&A process and inappropriate self-dealing between CEO Mickey Drexler and TPG.

Chancellor Strine of the Delaware courts described the situation as such:

“You're talking about -- in your own mind, as chief executive officer, you believe a real strategic option for the company is a sale. You're now using company assets. To the extent you're sharing nonconfidential public information, to the extent that you're tampering with employees and you're doing it without telling your board of directors first, icky kind of stuff.”

Icky indeed. Chancellor Strine was absolutely correct when he said, “This was not good corporate governance”. That’s probably an understatement to be honest.

What makes this case really special to study is despite some of the best governance people on the planet scrutinizing this deal, no one seems to consider or investigate Jim Coulter’s influence as Compensation Committee Chair and the role that may have played in swaying CEO Mickey Drexler towards doing a deal with TPG.

As we “connect the dots” on what happened here, pay extra attention to the timing of the 2009 and 2010 equity grants relative to the behind-the-scenes maneuvering that was occurring.

Connecting-the-Dots of J. Crew’s Compensation

The best way to “connect the dots” and highlight potential “dark” actions is to lay out J. Crew’s equity grants:

High Level Takeaways

Before we dig into the individual grants and layer in additional information disclosed in the Proxy Background of the Merger, a few high level takeaways and thoughts:

Equity grant dates are all over the place. If you see equity grants moves around like this, alarm bells should be going off that market timing “dark” actions may be at play. Remember that best practice is to grant equity after Q4 earnings. It’s hard to change grant dates this drastically these days, but you’ll still see a material change here and there.

Aside from the summer of 2008 grant (which in hindsight we know was a crazy time in the markets), these grants exhibit the characteristics of “spring loading” equity grants. Look at those beautiful post event percentage returns.

If you have high confidence a “dark” action (such as spring loading options) has occurred, it’s game on. You just have to be patient. Boards and management teams that engage in this stuff generally can’t help themselves going forward. It’s why “dark” actions tend to follow TPG around to other companies.

Mickey Drexler was considered a rockstar at the time so it’s reasonable to assume TPG wanted to keep him and his team happy. By maximizing compensation (possibly via spring loading), executives remain happy, TPG maintains a strong relationship, and it leaves the door open for working together again on future deals. In this case, the future deal ended up being J. Crew again.

Side note: Equity was granted via “unanimous written consent” which means the Chair of the Compensation Committee (Jim Coulter) has a lot of power setting the parameters of the equity grants and can get them approved fairly easily (and without much scrutiny) by the other Compensation Committee members.

Finally, you’ll notice the stock doesn’t really do all that much over the 4 years. There are “pops” but the stock largely bounces around in the $30s. Given this dynamic, there is usually an incentive and/or desire by the Board and Compensation Committee to “make it up to the team” to keep them motivated.

Overall, J. Crew serves as an excellent case to study “dark” actions given they are very exaggerated and easy to identify/critique. Modern “Dark Arts” tends to be much more subtle and takes a bit more effort to pick up on.

Let’s break down each year’s equity grant.

2006 Grant

J. Crew’s IPO occurred June 28, 2006 and granting equity ahead of Fiscal Year Q3 earnings in November feels oddly timed. Gut reaction is a “spring load” is happening given the off-cycle timing.

What’s interesting is this grant is occurred during the options backdating scandal and there was already a lot of discussion over spring loading being the next issue to pay attention to.

2007 Grant

The timing (May 2007 grant) feels weird again especially after giving executives equity 6 months prior in November 2006, but May grants are not that far off from when executives should be getting equity. The proper timing would be to align the grant with J. Crew’s Fiscal Year and grant equity in April (in my opinion) following Fiscal Year Q4 results.

That said, given the pop after November 2007 grants, you have to assume another “spring load” was in play.

2008 Grant

There’s quite a gap between the May 2007 grant and the July 2008 grant. What struck me about this July 2008 grant versus the prior grants is this one was granted nearly 6 weeks before earnings would be released in August. The previous grants occurred 1-2 weeks before earnings which makes it hard to consider it a “spring load” situation.

2009 Grant

Now this is when the grants start getting super interesting.

Did you know the SEC went after a J. Crew executive who was essentially trading on the same information that this equity grant probably relied on?

It’s funny that the SEC will crack down on open market insider trading, but won’t do a thing if the Compensation Committee (Chairman) uses the same information and grants management “spring loaded” equity. The SEC is basically saying “spring loading” is legal insider trading.

2009 was a crazy year to remember for anyone who was involved in the markets at the time. I generally believe “sell offs” create a situation where Boards try to incentivize management to stay motivated and spring 2009 was a “sell off” situation on steroids. This grant definitely has the vibe of “make up grant” and am not surprised by the massive earnings stock pop post grant.

Incidentally, CEO Mickey Drexler was also speaking to TPG about the feasibility of a buyout:

In the fourth quarter of 2008, representatives of TPG discussed with the Company’s management, on a highly preliminary basis, the feasibility of a leveraged buy-out of the Company, but concluded in early 2009 that market conditions, including for debt financing, would make such a transaction either not feasible or unlikely to proceed at any value that TPG believed would be sufficient to merit serious consideration by the Board, and there were no further discussions on the matter.

Think about that for a moment. Jim Coulter, as Chair of the Compensation Committee, granted equity to CEO Mickey Drexler around the same time TPG was discussing a J. Crew buyout without (I assume) the Board’s knowledge.

Now that is what I call a “dark” action to influence decision-making.

This grant arguably aligns Mickey Drexler’s interests with what TPG and not public shareholders.

2010 Grant

Given the “pop” history of previous grants and without knowing a buyout was on the table, the 2010 grant definitely had a “spring load” grant vibe even if the next earnings announce was weeks out.

That said, Jim Coulter isn’t even trying to hide what he’s doing with this grant. This grant did a spectacular job aligning management’s interests with TPG and not shareholders. Anyone who reads the background of the merger knows this has all the characteristics of a quid pro quo.

I assume the other compensation committee members and the Board would have absolutely rejected this grant if they were aware of what was going on behind-the-scenes between CEO Mickey Drexler and TPG co-CEO Jim Coulter.

It takes a lot of moxie to do this grant while simultaneously architecting a buyout with the CEO without the Board’s knowledge.

Another interesting angle to consider is other parties were expressing interest in acquiring J. Crew around this time:

On September 15, 2010, Mr. Drexler received a call on behalf of the chief executive officer of a company, which we refer to as Party A, during which Party A indicated its potential interest in a transaction involving the Company. Party A has contacted Mr. Drexler from time to time in the past several years to indicate its interest in a potential transaction with the Company, or to otherwise work with Mr. Drexler. None of these contacts ever developed into meaningful discussions regarding a transaction or other working relationship. Between September 15, 2010 and the execution of the merger agreement, Party A did not further contact the Company.

Did Jim Coulter knowingly grant equity to Mickey Drexler and the management team as a “good faith” act to win loyalty and ensure alignment for a TPG takeout?

When you lay out the timeline provided in the acquisition Proxy with the timing of equity grants, it paints a very “dark” picture of what happened here at J. Crew.

Conclusion

Overall, no one is going to dispute the comfort and familiarity CEO Mickey Drexler had with TPG and his desire to work with them again. There is a long history between TPG, J. Crew, CEO Mickey Drexler, and TPG co-CEO Jim Coulter.

Where things get murky, daresay “dark”, is how much of a role did Jim Coulter’s peculiarly timed equity grants (especially the 2009 and 2010 grants) influence Mickey Drexler’s decision-making and effectively force the Board to accept TPG’s takeout offer?

Very clever Mr. Coulter. Very clever.

So if you wonder why I’m always on high alert when I see a TPG executive serving as the Chair of the Compensation Committee, it all started with J. Crew.

Up Next: More Case Studies

Up next will be more case studies! I haven’t decided if I want to do another TPG case or something else. We’ll eventually cover all the important ones. It’s just a matter of the order. See you at part 3 soon!

Great article...a year later it's still timely. Would be interested to know if your tracking TPG involvement with ESGC? Any thoughts?